The word “pacifism” is certainly not the same as “passivism,” though I used to associate the two. The word “pacifist” stems from the Latin root pac, meaning “peace” and fic, meaning “making.” The Latin root of the word “passive” is passivus which means “capable of feeling or suffering.”

I am currently wading through a thick sea of memos (notes that I wrote during and after conducting focus groups). I’m simultaneously coding and re-coding the data in order to piece together themes that are supposed to “emerge” from it. I spent almost a solid 96 hours last weekend pushing my way through these transcripts and notes, splashing around and drowning in the words of my participants. My participants include family members of parents and other primary caregivers of pediatric palliative care patients (kids with life-limiting illnesses). There are a few things that I just can’t keep to myself. It would be socially unproductive.

The topic of my research is “Quality of life” or “wellbeing.” What makes one’s life one of high quality? Anyone who does not believe in the immediate applicability of health research only need listen to one of my brave research participants for five minutes (I’d recommend the same regimen for people who think they’re “busy” with things of importance… but I’m digressing).

Their stories highlight the importance of separating pacifism from passivism. The focus groups I conducted contained only parents who care for children with debilitating illnesses, most of which change the way the children look and act, altering the way society perceives them. Many of the kids are severely developmentally delayed, but not unaware (yes, a double negative; I’m sorry!) of what is going on around them. The parents’ words really speak for themselves, but for the purpose of keeping them de-identified I’ve changed all but the essence…

In one of my first groups, a mother spoke about the frustration of communicating with people who are not used to being around children with disabilities:

Mother 1: Some people stare at my kid like he’s from a different planet. It’s insulting. I didn’t used to have a kid with disabilities and I’ve learned so much about other people though this process. Most of them have no idea how to behave when they see people like my son. They are uncomfortable and squeamish.

Mother 2: Society only knows how to stare. They just stare and get progressively more uncomfortable. They don’t like seeing how I feed him in restaurants, but I do it anyway because they have no right to turn us away. I’m not going to leave. We’re going to stay here and eat dinner. If you don’t like it, you can leave.

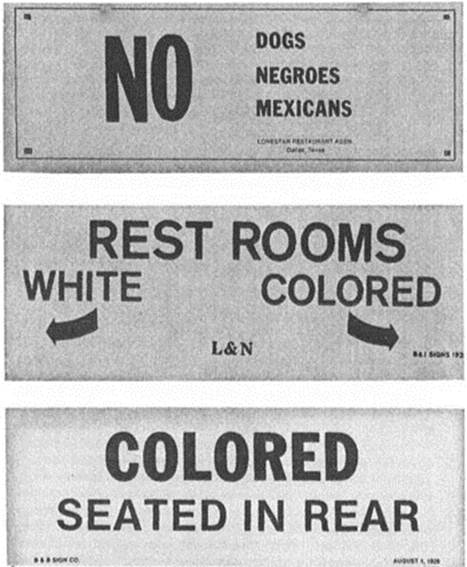

Does this sound familiar, my fellow observers of MLK Day (two weeks late)? Even some doctors don’t seem to get it:

Father 1: I take my daughter to the doctor sometimes and the nurses don’t acknowledge her as a person. They stick things into her mouth and body. They move her clothes out of the way and look down her. I want to shout, “Hey! Hey! Warn her before you do that!” She doesn’t understand everything, but she knows where she’s at and can sense when things are going to happen if she is warned.

I used to believe that you couldn’t be prejudiced without opening your mouth. I really trusted the quote, “Sometimes it’s not what you say; it’s what you don’t say that matters.” But that is not true. Communicating with everyone, even those you don’t feel comfortable communicating with (yet), is key. Do I know how to communicate with every child that I conduct research about? No, of course not. However, I am learning very quickly that a little smile and a positive, nonjudgmental attention is a fairly universal language of peace.

One last chopped quote: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will …be judged …by the content of their character.” – Martin Luther King, Jr.

Images from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/8-surprising-facts-about-mlk/2013/01/16/c37ec6ee-6005-11e2-9940-6fc488f3fecd_gallery.html

http://www.abhmuseum.org/2012/10/the-five-pillars-of-jim-crow/