My second day volunteering for Mother Teresa’s successor (Mother Mercy Maria) begins as they all do: With a sunrise walk through the streets of Kolkata, a prayer at the Mother Teresa convent, a breakfast of bananas, bread and chai, and a bumpy, life-threatening bus ride to the girls’ home, Shanti Dan. Most days thereafter follow a predictable pattern of squeezing the open palms of girls who appear starved for attention, washing clothes, singing, teaching, feeding lunch, and putting the girls to sleep. At lunchtime, volunteers (called “Aunties” by the girls) learn to be mother birds: picking bones out of the fish curry that is poured over rice and spoon feeding or making sure they eat it all (with their hands, as is customary in that region).

Between 8:30 and 10:00am, volunteers scrub and wring out the girls’ clothes by hand in long troughs. We work swiftly with the local women who are employed by the house. We then climb 40 stairs with buckets of blankets, towels, night gowns, shirts, etc. to hang dry on the rooftop. It was here that I learn the intensity of the phrase “like wringing out a wet blanket.” Everyone should try wringing out at least one blanket in their lifetime. It’s infinitely easier if you have a partner to play tug-o-war with.

The resident girls are supposed to help with the washing process. One of my favorite girls, Asha, was my shadow this morning. She’s a beautiful, smiling child who probably has Downs Syndrome. All she wants is someone to love and pay attention to her; two very easy things to do. She greeted me on my first day with a big smile and a hug and persistently patted the seat next to her for me to sit on each time I passed by. This morning, she smiled wider than I knew was possible when I grabbed her outstretched hand and laughed animatedly when I counted her footsteps up and down the stairs to the rooftop where laundry is hung.

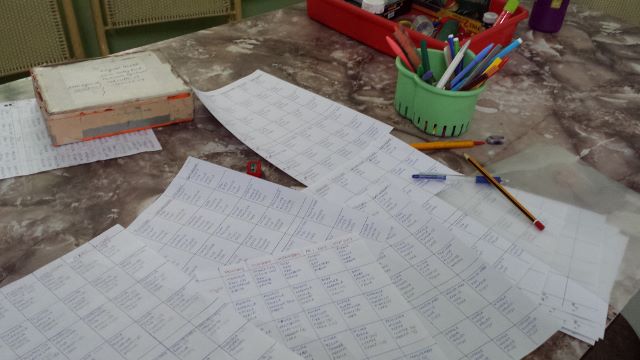

Just as I was starting to feel excited that the laundry was finished and the singing and “play therapy” was about to begin, one of the nuns called to me. “Auntie! Can you write in English?” I nodded and asked how I could help. She handed me a list of the children than received physiotherapy and told me to copy it onto 20 sheets of paper. My head spun a little. That would take hours. “Can you finish today?” she asked. I doubted it.

As I copied the girls’ names over and over on the papers, I reflected on the inefficiency of the daily tasks performed at the home. The homes are run without laundry machines, dishwashers or copy machines. Humans perform these tasks, despite the 64 girls that I believe would benefit far more from their intelligent attention. However, the philosophy of Mother Teresa’s order dictates that her followers live among the poorest of the poor and not above them. We are not here to save people, but to hold their hands and walk with them. Since they all come from poverty and simplicity, it is through those states we stride. I tried not to think of the 1 rupee I’d paid for a copy of my visa the day before and copied the girls’ names over and over.

My cohort of volunteers included girls from Australia, Korea, Taiwan, France, Spain, Portugal, China and Japan. We spoke Spanish on the first day since there were more Spanish than English speakers and most of the mashis only speak Hindi. A volunteer from Belgium came and sat next to me. She worked with the physiotherapists to stretch and strengthen the girls. As we “Xeroxed” away with our hands, she told me about the relaxed philosophy of Shanti Dan. In Belgium, she saw about 20 patients each day. At Shanti Dan, she worked with about five girls each morning and was constantly being told to take a break and rest. “‘Auntie! Why are you working so hard?’ zhey tell me,” she said in her charming Belgium accent, “Everything I do, though, I can now do wit feeling. I have zhe time to really und-herstand zhe guhrls.” The slower pace allowed her to feel less stressed and focus on things that matter: keeping everyone safe and nourished with more than just boneless curry, using human tools and unaided by financial incentives.

“Asha” means “hope” in Hindi (and different types of “hope” in different contexts). Interestingly, it was the most common name I encountered on the rest of the journey.