By Josiah Beharry, Graduate Student Researcher, Center for the Humanities, UC Merced

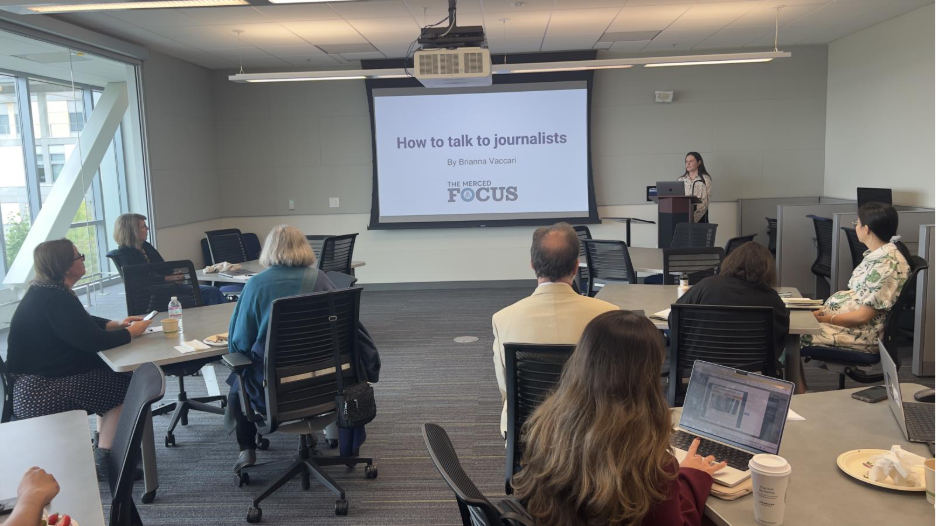

There’s a quiet art to being interviewed. Most people don’t think about it until a reporter is standing in front of them, notebook open, recorder on, waiting. That moment can feel like you’ve lost control of the narrative—but as Merced Focus journalist Brianna Vaccari reminded a room of UC Merced faculty, students, and staff last week, it doesn’t have to be that way.

Vaccari, a longtime Central Valley reporter, has spent over a decade telling stories about the region she calls home. At this workshop, she wanted to make something clear: talking to a journalist should feel like a collaboration, not a confrontation.

Too often, people assume they have no agency once a reporter calls. But the first lesson Vaccari shared was simple: you can always say no. You don’t owe anyone your story. You can ask questions before you agree to an interview, about the topic, the angle, who else is being interviewed, or when it’s running. These aren’t defensive moves; they’re the groundwork for trust.

She also explained one of the most misunderstood parts of journalism: “off the record.” It isn’t a magic phrase you can invoke after you’ve already spoken. Both sides have to agree before the conversation begins. If they don’t, everything you say is fair game. “Off the record,” she said, “is a mutual agreement, not a retroactive request.”

When the interview does happen, it’s okay to set conditions. You can discuss when, where, how long, and whether it’s recorded or filmed. Most journalists prefer to record to ensure accuracy. “I can’t write as fast as people talk,” Vaccari admitted. But you have the right to know when it’s happening. California law requires two-party consent for private recordings, meaning everyone involved has to agree.

Once the story is published, your role doesn’t end. Vaccari encouraged everyone to read their quotes, check the context, and reach out if something seems wrong. “Accuracy, accuracy, accuracy,” she said, quoting an old newsroom mantra. Good outlets will correct mistakes publicly.

The session also touched on what happens when things go wrong. Sometimes a headline oversimplifies or a single comment becomes the story. Vaccari said the best thing to do is reach out directly to the reporter, explain your concerns, and request a correction if it’s factual. If the issue is about framing, you can still ask for clarification or additional context. What you can’t do, once the story is out, is take it back entirely.

The conversation eventually turned toward how faculty and community members can build better relationships with local media. Vaccari said journalists value experts who can translate complex ideas into plain language. The goal isn’t to sound rehearsed or academic, it’s to connect with everyday readers. She also emphasized that journalists, like their sources, operate under pressure: tight deadlines, limited staff, constant competition for attention. “The more information you can give us upfront,” she said, “the better your story will be.”

Several faculty members asked about the difference between local and national media. Vaccari described Merced Focus as serving “casual news consumers”: residents who scroll through stories on their phones, not people reading policy papers. “Our audience lives here,” she said. “We want our stories to matter to someone going about their daily life in Merced.”

Another question lingered over the discussion: should journalists take a stance on social issues? Vaccari’s answer was clear. “I’m not the community’s voice,” she said. “My job is to pass the mic.” Objectivity, she explained, isn’t the goal; fairness and accuracy are. Journalism’s strength comes from transparency and depth, not from pretending reporters have no opinions.

By the end of the session, what emerged wasn’t a set of rules but a kind of mutual understanding. Reporters have a job to do, and so do sources. Both depend on honesty, preparation, and respect. Talking to a journalist doesn’t mean surrendering control of your story – it means learning how to share it responsibly.

For those interested in seeing how that work plays out, Vaccari encouraged everyone to follow Merced Focus, a nonprofit newsroom covering issues that shape life in the Central Valley. Their stories are free to read and republish, reflecting the belief that information, like trust, shouldn’t sit behind a paywall.