Mabel Orjuela-Bowser, Ph.D. Candidate, Interdisciplinary Humanities, UC Merced

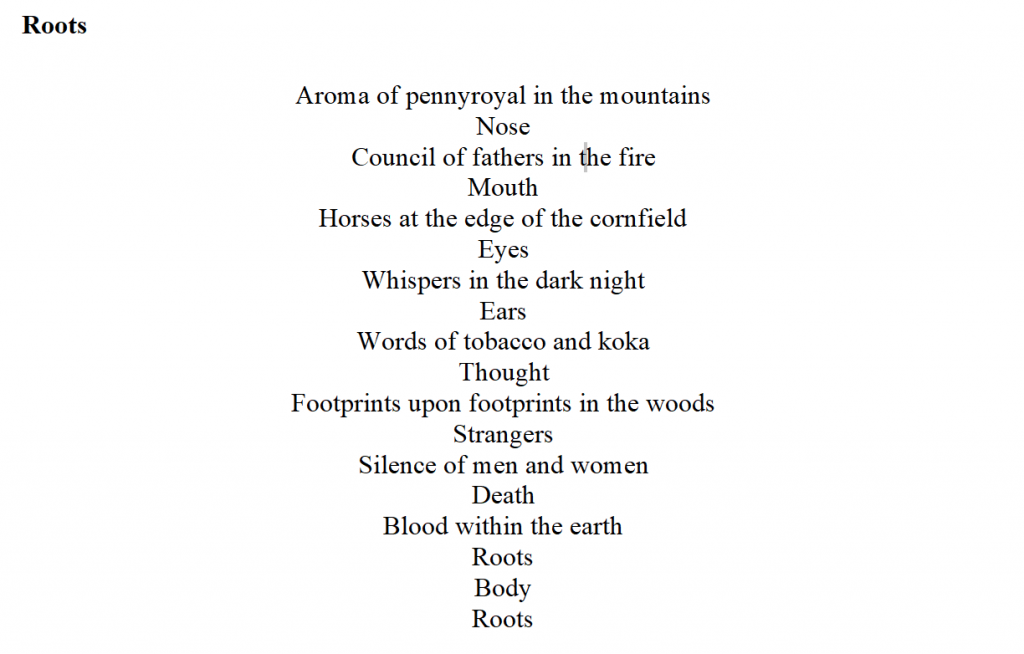

Fredy Chikangana generously gave me his original manuscripts of nineteen poems written in Quechua, some of which were recently on display at the UC Merced Library, together with more that I share here, accompanied by their Spanish version and my own or other English translations. While some of the poems are about the 2021 social outbreak in Colombia, others are about different topics. I was glad to find among them a few of his iconic poems such as “Quechua es mi corazón” (Quechua is my Heart) and “Espíritu de pájaro” (Bird Spirit).

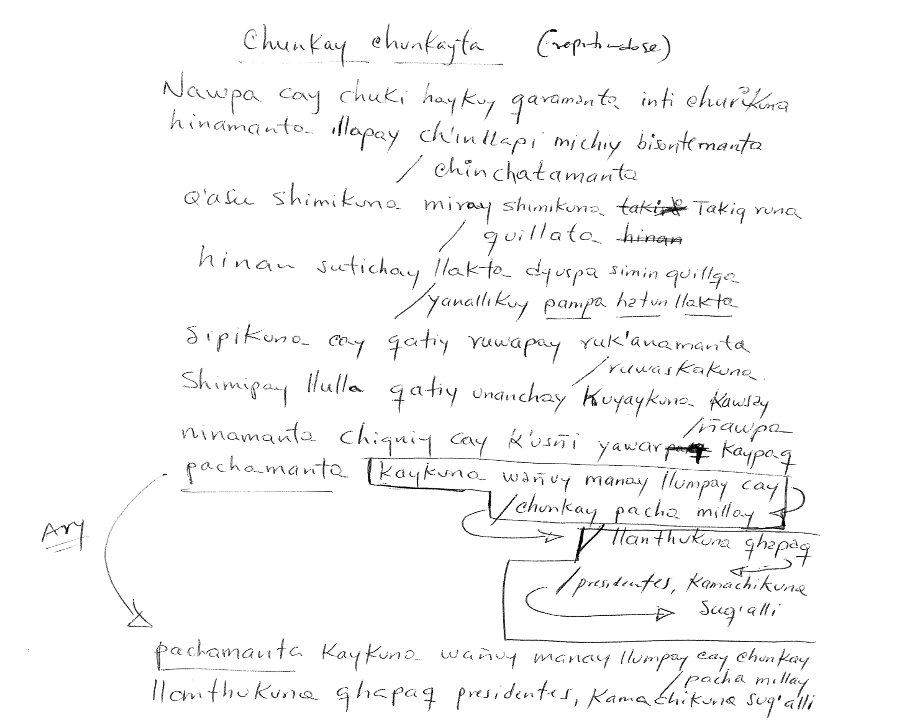

Figure 1: Photo of the manuscript of the poem “Chunkay chunkayta,” from the author’s personal file

This is the original manuscript of the poem “Chunkay chunkayta” (Repeating Itself), written in Quechua Runa Shimi language. However, the words “(repitiéndose),” and “presidentes” are written in Spanish. In the first line, we can read “(repitiéndose),” in parentheses, which is the Spanish translation of the title “Chunkay chunkayta.” The use of the word “presidente” is probably because it does not have an equivalent in Quechua Runa Shimi language, as there is no such a figure in their culture. Some of the most common words to refer to a Quechua chief or chief communal authority are “kuraka” and “Pushak,” but they are not exactly equivalent to a Western president.

In “Chunkay chunkayta,” Chikangana establishes a genealogy of current power in Abya Yala (today known in Spanish as Las Américas) to show us that the invading civilization and its power have been repeating and adapting to the changes of the times, but without losing its true essence of domination in order to maintain its privileges.

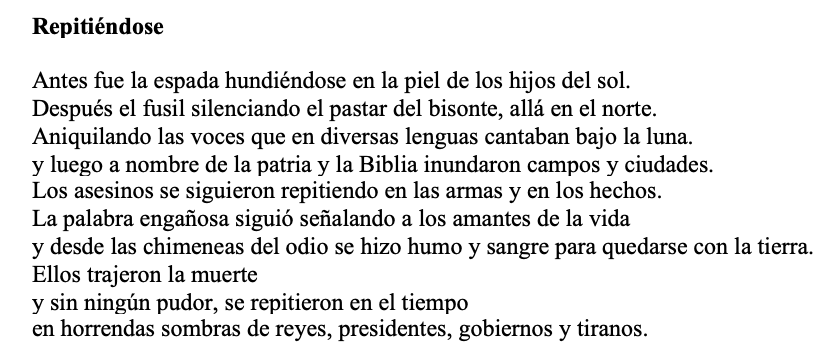

The poem is unpublished, so there is no printed version in Spanish. With the author’s permission, I transcribe here the version that he read in Spanish at the Poesía en Resistencia event on May 28, 2021, followed by my own translation.

Figure 2: Photo of the poem “Repitiéndose”

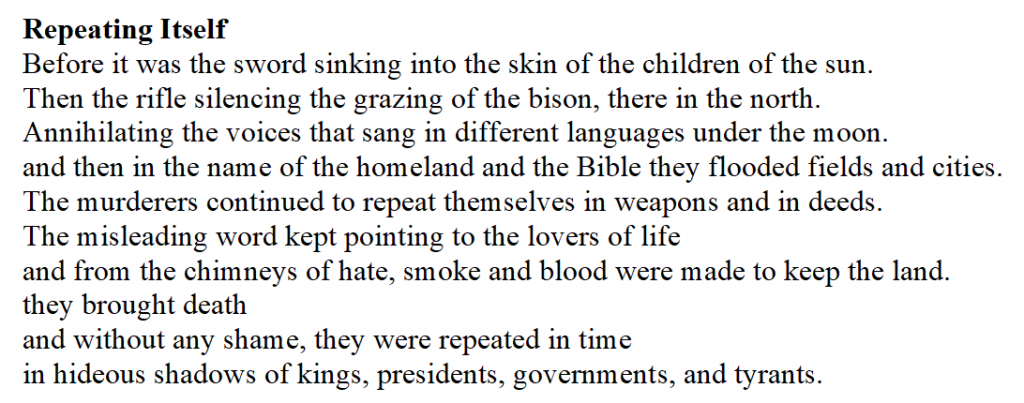

Figure 3: Photo of the poem “Repeating Itself”

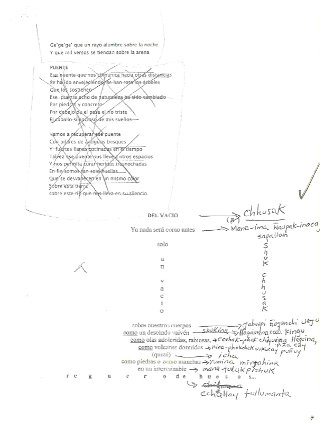

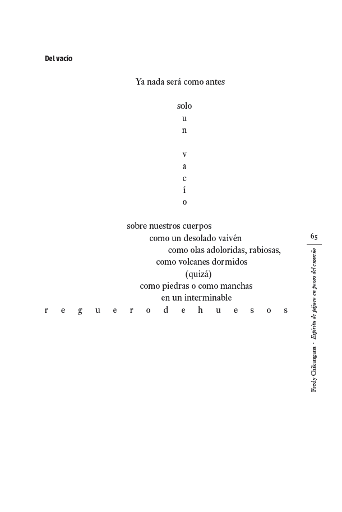

Figure 4: Photo of the manuscript of the poem “Chhusak,” from the author’s personal file

Chikangana initially writes his poems in Quechua or Spanish, to later translate them into the other languages (Spanish or Quechua). Other times, he writes and translates at the same time, or writes in both languages simultaneously, implying that each version of the poem is an original creation, rather than a translation. This manuscript suggests that the poet translates, line by line, the poem into Quechua after it was originally laid out and written in Spanish in 1990.

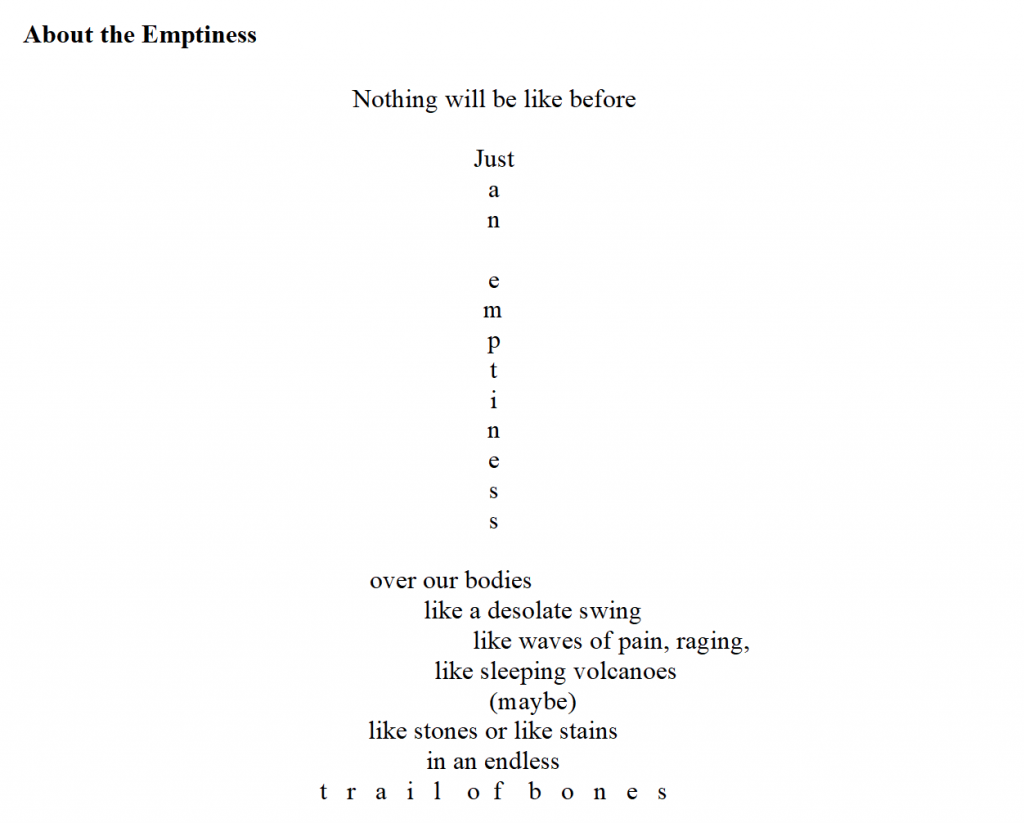

This calligram expresses the feeling of emptiness experienced by the lyrical voice, the original peoples of Abya Yala, and all colonized subjects. The poem symbolizes the rupture of a world’s harmony due to the colonial experience.

Figure 5: Photo of the poem “Del Vacío”

Figure 6: Photo of the poem “About the Emptiness”

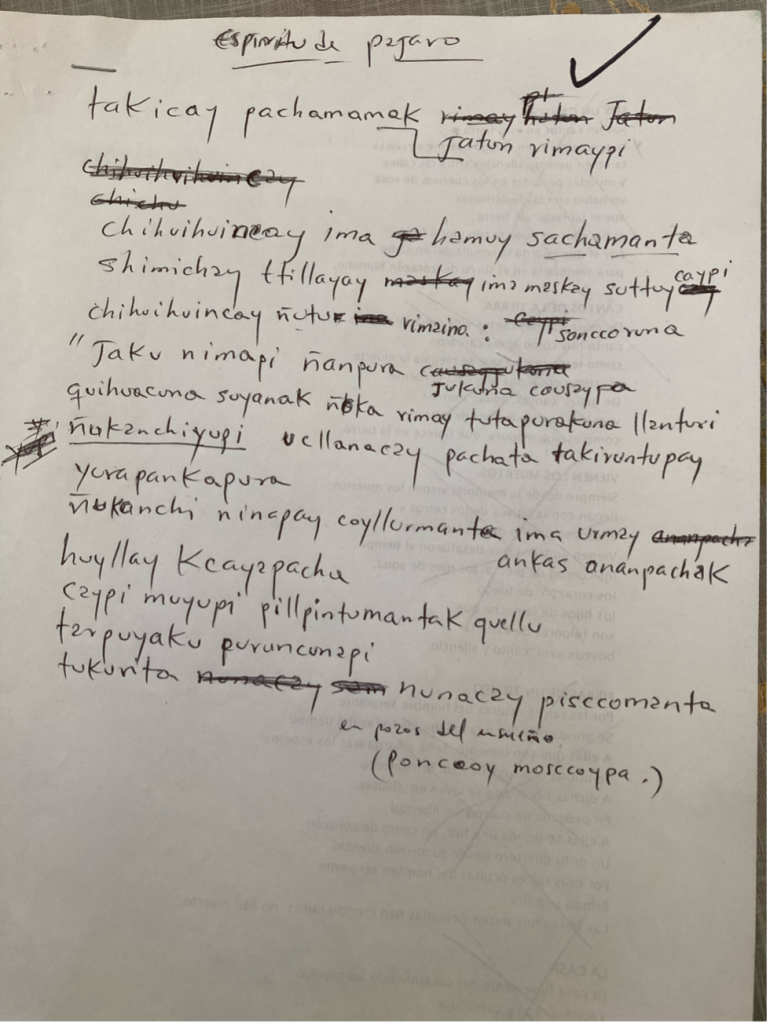

Figure 7: Photo of the manuscript of the poem “Samay Pisccok,” from the author’s personal file

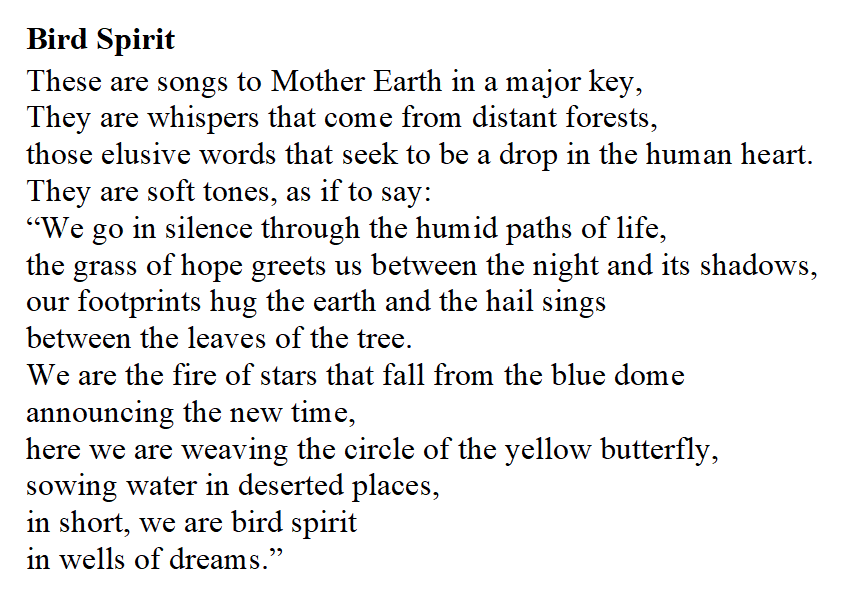

In this original manuscript, the poem appears written in Quechua. However, the title “Espíritu de pájaro” and the penultimate line, “en pozos del ensueño,” are written in Spanish. This suggests not just a blend of words and grammar from two languages but a writing produced in a space where one feels, thinks, and writes in a kind of Spanchua (following the idea of Spanglish). The last line, in parentheses, seems to be the translation to Quechua Runa Shimi of the verse “en pozos del ensueño.” The author, in his own voice and that of his ancestors, sings joyous songs to the Pacha Mama (Mother Earth). He aspires with them to move the human heart for his community to preserve its Quechua roots while moving in a border space, to preserve the Andean spirit of the condor, and together weave a new era, an intercultural era.

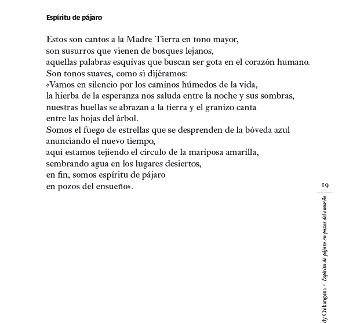

Figure 8: Photo of the poem “Espíritu de pájaro”

Figure 9: Photo of the poem “Bird Spirit”

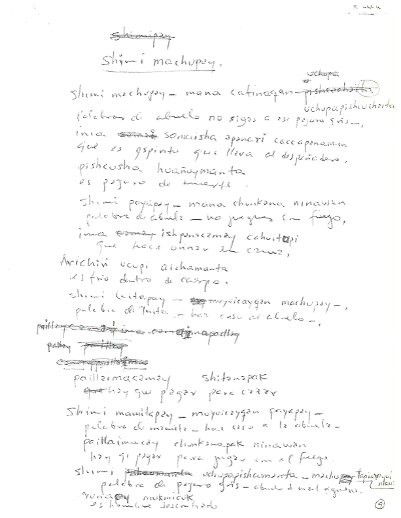

Figure 10: Photo of the manuscript of the poem “Shimi machupay,” from the author’s personal file

On this original manuscript, the poem appears written simultaneously in Quechua and Spanish. Each verse in Quechua is followed by its equivalent in Spanish. This technique appears in several of the poems in this collection.

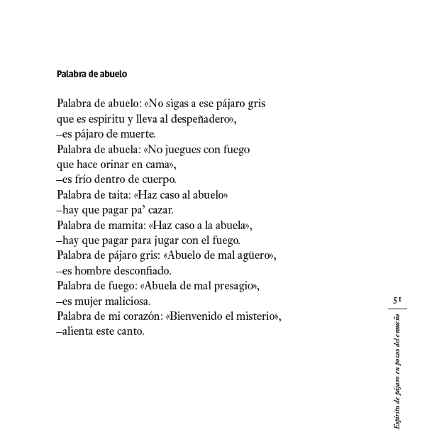

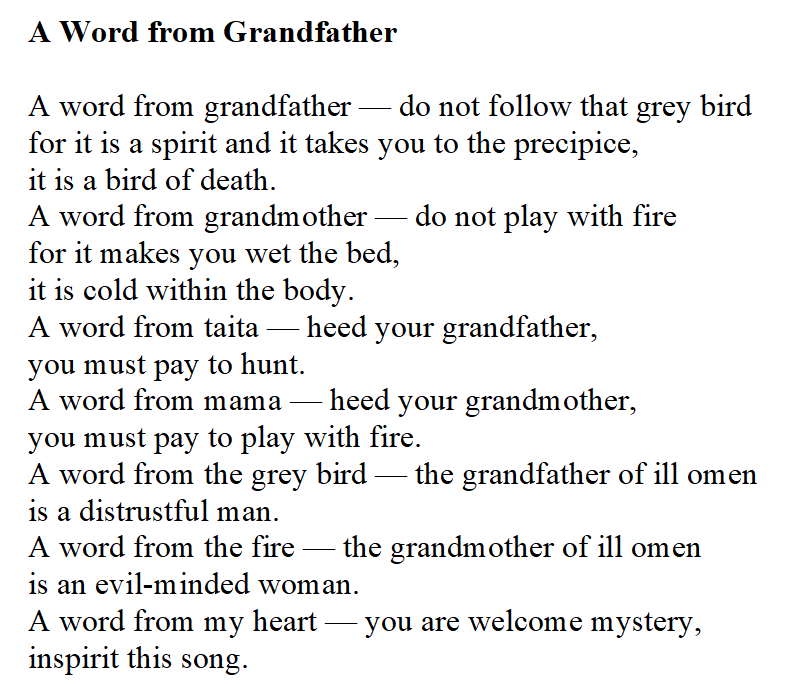

“Shimi machupay” evokes the proverbial voices of the elders and ancestors, the local knowledge that is based on the wisdom of nature and of physical and spiritual living beings. The lyrical voice embraces mystery, opens hearts to listen to what Pacha Mama (Mother Earth) has to teach us, her advice, and her guidance for life.

Figure 11: Photo of the poem “Palabra de abuelo”

Figure 12: Photo of the poem “A Word from Grandfather”

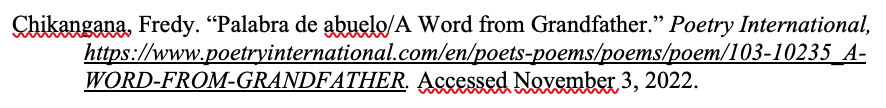

Figure 13: Photo of the manuscript of the poem “Takina,” from the author’s personal file

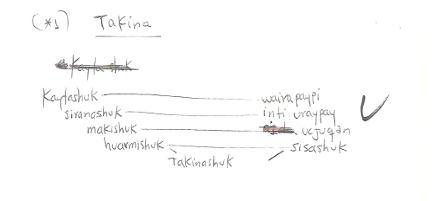

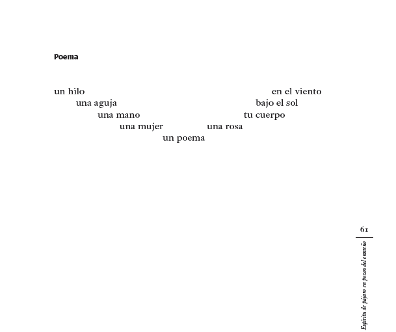

This is the manuscript of a poem written in Quechua, without any translation. However, the Spanish version appears on the book Samay Pisccok Pponccopi Mushcoypa / Espíritu de pájaro en pozos del ensueño (61). “Takina” is a poem built on a double staircase of images that descend from the left and from the right towards their center, to meet in “a poem.” Both staircases of images relate the woman to a poetic act. As a mother weaver of the community and as a woman in the private sphere.

Figure 14: Photo of the poem “Poema”

Figure 15: Photo of the poem “Poem”

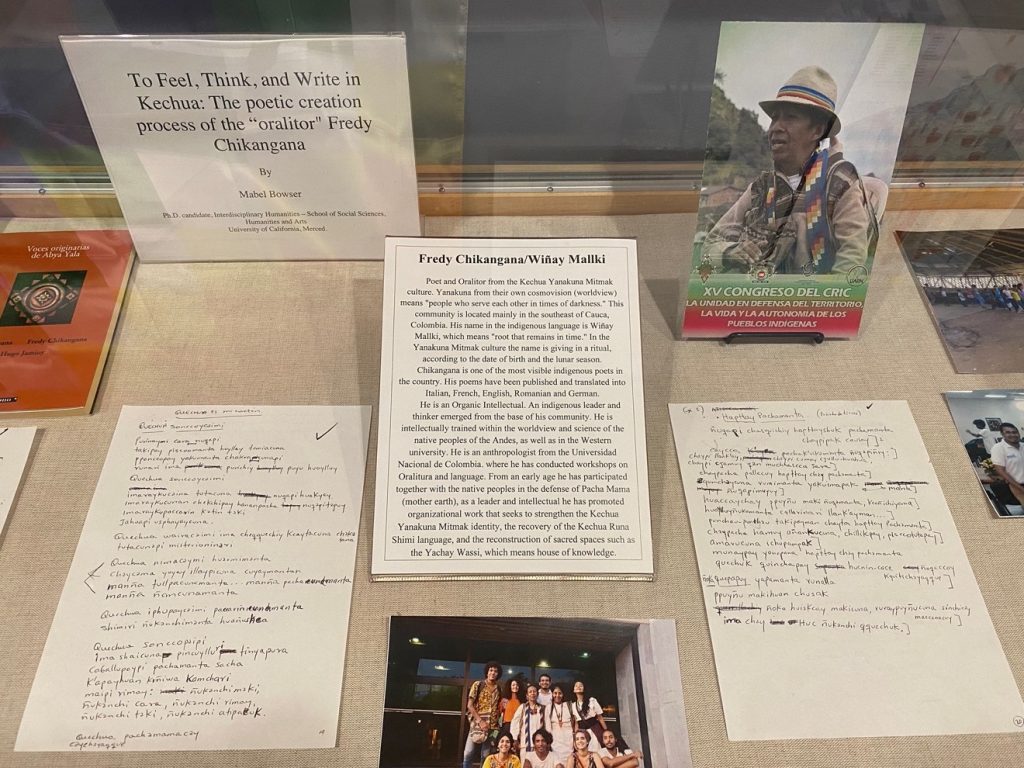

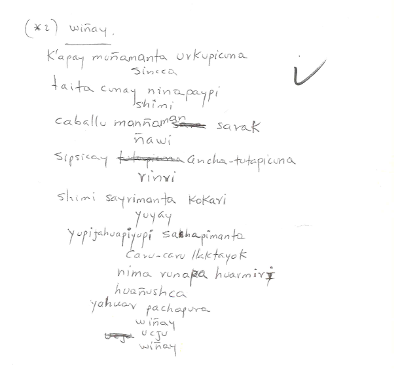

Figure 16: Photo of the manuscript of the poem “Wiñay,” from the author’s personal file

This poem gives us images of the Yanacona, a sensory people (“nose”, “mouth”, “eyes”, “ears”), who produce thought, knowledge, and wisdom in their communication with sacred nature (“tobacco and koka”). The harmony of their world was shaken by the invasion of Abya Yala and, in particular, by the invasion of the Andean worldview due to violence (“strangers”, “blood”, “death”) and the forced migration to the Western world. However, they retain their true roots.

Figure 17: Photo of the poem “Raíces”

Figure 18: Photo of the poem “Roots”