By Ivan Gonzalez-Soto, Doctoral Student, UC Merced

Prior to COVID-19, I used critical race and ethnic studies, history, and environmental studies to frame my research on water, racialized labor, and agrarian capitalism in the 20th-century US west. Recently, I’ve added another lens through which to understand my research questions: the graphic novel. Allow me to illustrate.

During the Spring 2020 semester, I enrolled in a graduate seminar titled “Race, State, and Power” and met once a week with peers to discuss books on global insurgencies, racial capitalism, and the nation state. Unbeknownst to me then, our course readings—which paired critical history with speculative fiction—would set two creative projects in motion which helped me cope with the state of the world while pushing the limits of what I thought reflected a good/traditional dissertation project.

Over the past months, I’ve used art and speculative fiction to cope with declension narratives and doom and gloom statistics that envelope the present moment. Fiction by Octavia E. Butler, Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi, and Fernando Flores have shown me how to interpret the past, present, and future in ways I had never imagined. Their stories, albeit odd, offered respite when I needed it most. Most importantly, their novels helped me hang on to a future in which things eventually do get better. I imagined I could be, as the non-profit online magazine Grist eloquently writes, “working toward a planet that doesn’t burn, a future that doesn’t suck.”

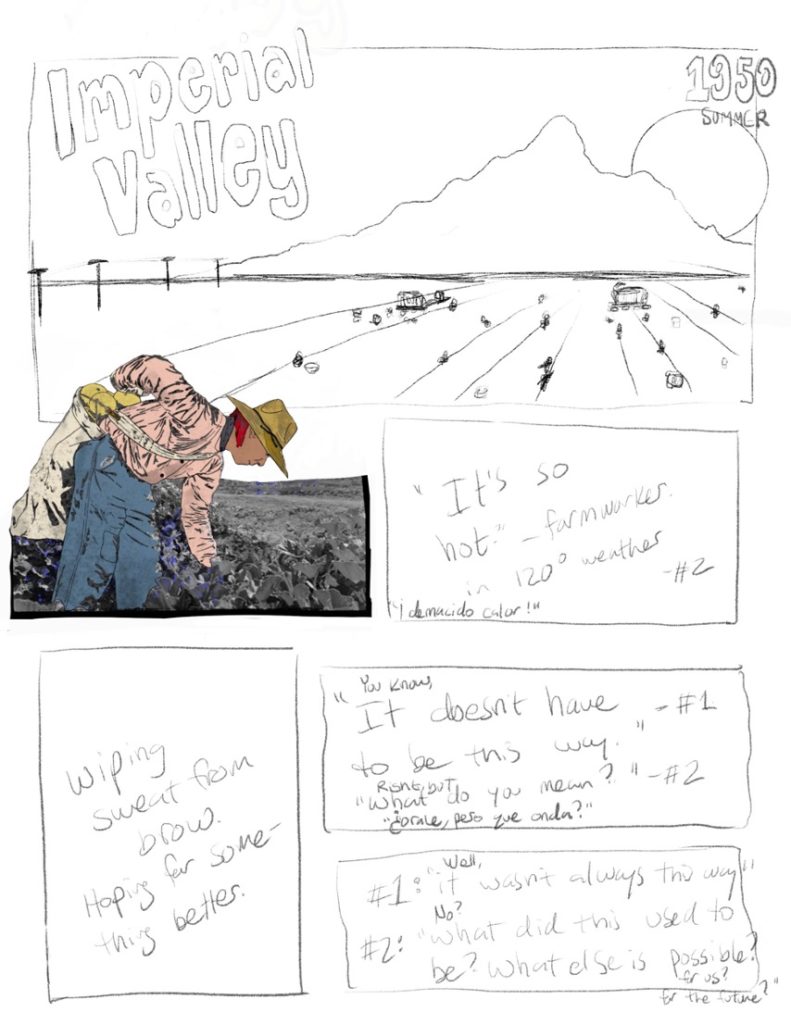

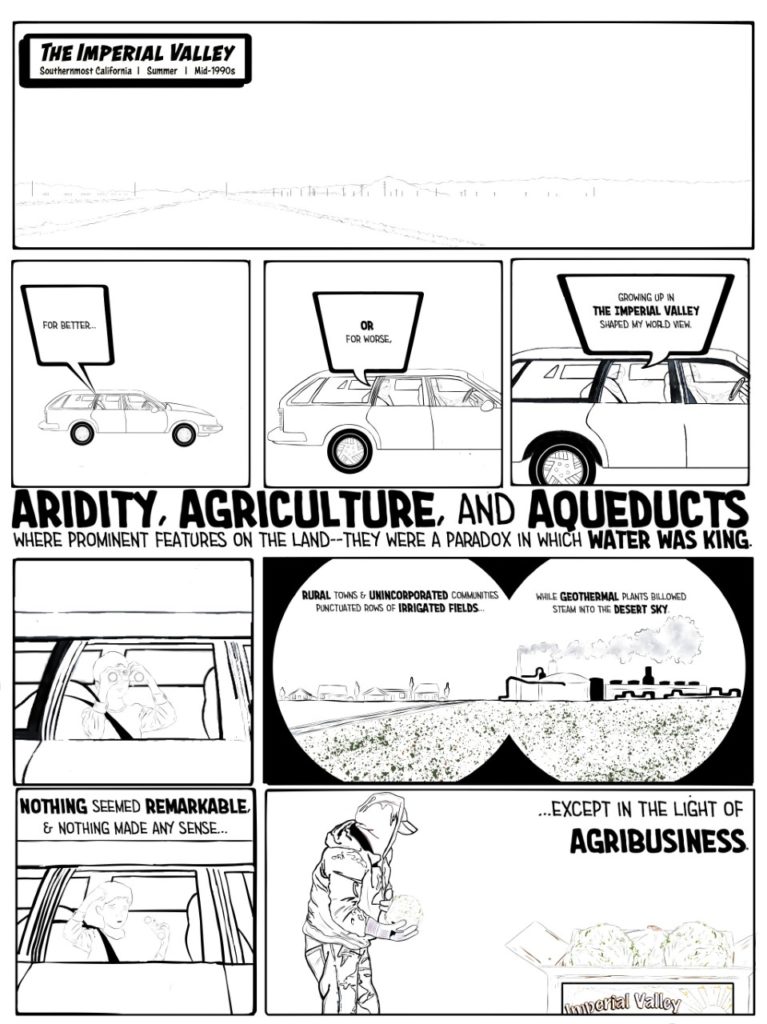

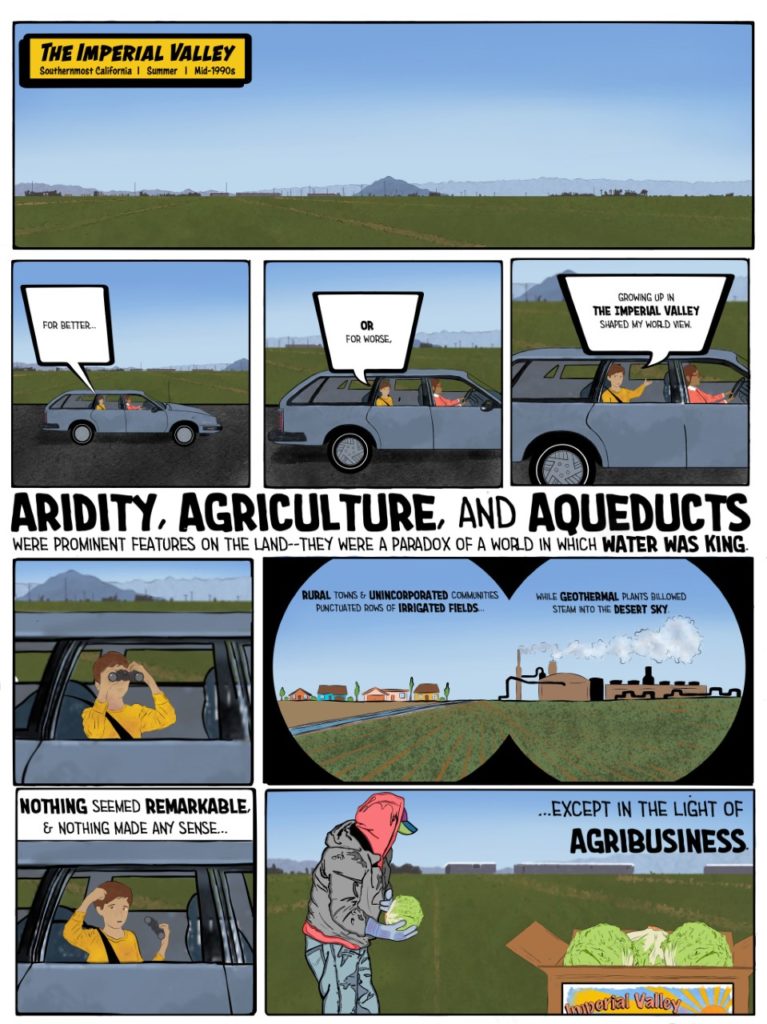

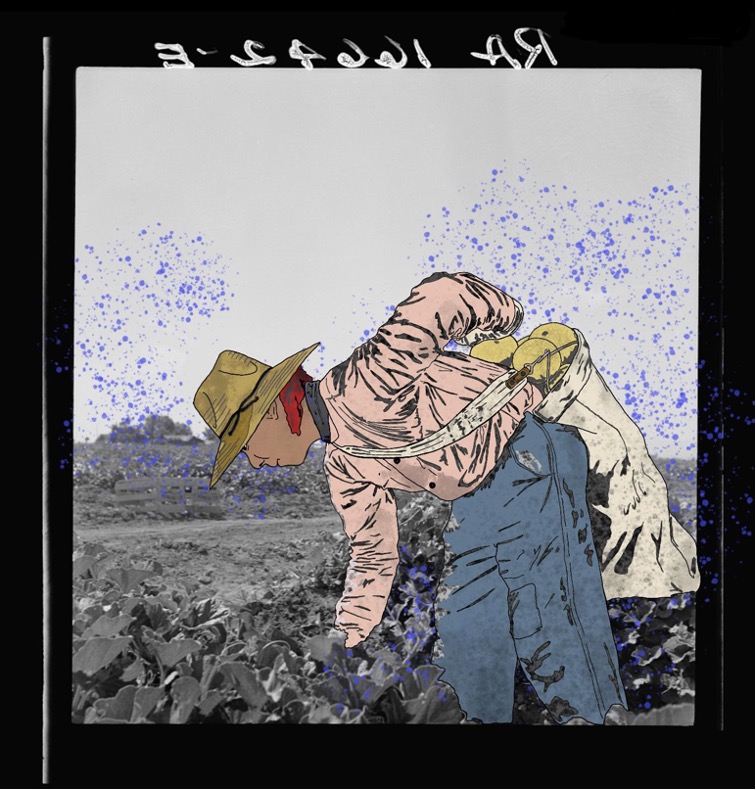

The closure of archives during the pandemic resulted in unexpected changes that challenged me to brainstorm other research methods for my work. All the while, I searched for opportunities to broaden the scope of my work through creative perspectives. This has manifested as a creative outlet wherein I illustrate scenes from the archive. Examples, like my illustrations below, merged mid-twentieth century black and white archival photographs in the public domain with colorful renditions that brought the archive to life. The sample illustrations below are creative drafts in which I incorporated storyboards, dialogue, and historical references to emphasize key elements in the histories I’m exploring for my dissertation.

I will still write my dissertation in the academic prose expected of doctoral research. However, the graphic novel component I’ve envisioned has the potential to reach an entirely new audience that may not have an interest in reading standard, double-spaced, 12-point, Times New Roman, linear text. Together, the traditional dissertation and artistic renditions offer an innovative form of storytelling.

In line with the creative aspect of this work, I’m using graphic history to share my work while imagining alternatives for a better future through speculative fiction. That is, I’m blending history with imaginative fiction to think of how problems of the past can be addressed and abolished in the future. In this way, I am able to explain past issues while imagining alternative futures in which things get better. Themes such as labor exploitation in agricultural fields, environmental degradation due to toxic pesticides, and the expansion of prisons and militarized border walls can be written out in the speculative futures I’m writing about. This helps me find hope through abolitionist alternatives to get to the world I want to be a part of. And while it may seem idealist, the pandemic has reminded me that I must imagine alternatives with a better future to stay hopeful.

Unlike the archival photographs that captured Imperial Valley farmworkers as nameless and faceless subjects (see original photograph here), my illustrations help breathe new life to the workers’ struggle by centering their lives in local history. This approach speaks against dominant discourse and regional histories which alienate and render workers invisible to the land. This erasure is a trend in mainstream history, but I believe the workers’ stories in the Imperial Valley are out there—even if their stories aren’t necessarily preserved in the traditional archive. As a creative project, I’m formulating the past through speculative historical fiction to center the agency of Imperial Valley’s working class alongside a brighter future. Indeed, the workers have a story to tell; they’re there—even though the archive suggests otherwise.

Other illustrations, like the special collections box below, have the potential to communicate the research behind my work. While I couldn’t take my readers to the archive reading rooms, I can illustrate what and how I saw the archive in ways that a footnote simply could not. There’s hope in the dissertation-research-turned-graphic-novel approach because it helps the public visualize the past to shape a better and more just future. In the process, the speculative approaches in this work might help speak more just futures into existence.

Because many archives closed temporarily or were shuttered completely, I was forced to adapt my research into something more accessible. And to cope with declension narratives that enveloped this last year, I’ve turned to art and speculative fiction to make sense of my research through new angles. I’ve since collaborated on a reader-friendly environmental justice comic book on the right to clean drinking water based on a fictional town in California’s Central Valley. It explores my research through fictional characters in ways that bar graphs, charts, and conference presentations could not. That little comic book is now a resource for rural communities of color in the San Joaquin Valley and it’s publicly available through eScholarship. Projects like these are the result of finding ways to cope with the pandemic while getting creative in the process, and I hope to connect with others out there interested in similar work.