by Dorie Perez

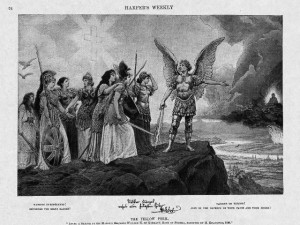

“I’d sit at the back of the room to present this paper,” said Rhea Riegel, a doctoral student in the Interdisciplinary Humanities graduate group and a 2014-2015 Center for the Humanities Graduate Fellow, “but that’s not what a real trickster does.” Real tricksters, like the infamous literary figures Puck from the plays of William Shakespeare and Robin Goodfellow, the archetype that Robin Hood is based on, do their dastardly deeds with an eye towards the future. Riegel says they offer an example of alternative behaviors where social change fosters a rethinking of social roles during moments of upheaval. Tricksters do the important work of challenging or, invariably, reinforcing social roles and morays that the public must then reproduce.

Riegel’s work on Early Modern English literature includes the literary canon of Robin Hood, known to 17th Century readers as Robin Goodfellow. Robin Goodfellow’s “punishment” for bad behavior is to reset “wrongs” – lecherous uncles are whipped and bawdy women dunked in duck ponds to the delight of spectators learning a collective lesson. Humor itself is seen by scholars like Riegel as setting up social conditions for commentary or a rethinking of codified relations. The types of humor that tricksters use are up-ending, but not the full satirization of current events that the modern reader may be accustomed to. Satirical activism as a brand of humor is distinct from situation comedy. Whereas satire disrupts, comedy reaffirms social “truths”. Allegorical tales of lessons learned – Robin Goodfellow punishes rather than scolds, acts rather than relays messages like angels and other divine messengers – making his role in Western literary tradition social rather than based on religious canon or politically attuned to current events of the Early Modern era. His actions serve, in the Foucauldian sense, as correctives of behavior, a task seen as a shared social responsibility.

Another trickster figure Riegel centers her study on is that of Moll Cutpurse, a composite character purportedly based on a real figure in history who challenged gender norms by dressing in masculine clothing to trick unsuspecting targets. Cutpurse becomes the embodiment of changing gender norms during a period of intense social upheaval. The events of the 17th Century in England were incredibly disruptive; the English Civil War, religious strife among warring Catholics and Protestants, the Great Fire of London and the death of Charles I on the orders of a newly-empowered Parliament served as unsteady social ground to negotiate. Trickster figures flourished in the work of William Shakespeare and his contemporaries as ways to reorient audiences to a dynamic reality of changing norms they would then need to make sense of.