By Josiah Beharry, Graduate Student Researcher, Center for the Humanities, UC Merced

In times of loss and struggle, joy is often treated as an afterthought—something fleeting, maybe even indulgent. But what if joy is not a luxury at all? What if it is the very condition that allows communities to resist, endure, and imagine beyond the limits imposed on them?

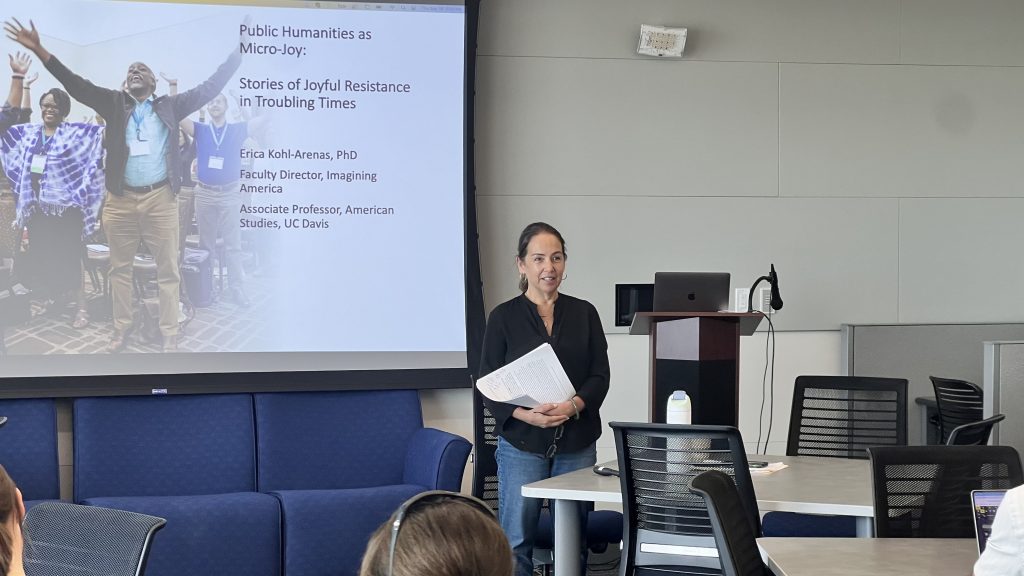

That question ran through Erica Kohl-Arenas’ presentation, “Public Humanities as Micro Joy: Stories of Joyful Resistance in Troubling Times.” Her reflections—grounded in decades of collaborative work and long-standing partnerships with the Pan Valley Institute (PVI) in California’s Central Valley and the Mississippi Center for Cultural Production (Sipp Culture)—showed how joy lives at the center of community survival from California to Mississippi.

Their shared projects—poetry slams in historic theaters, immigrant-led cultural festivals, and community farms reclaiming abandoned main streets—remind us that joy is more than happiness. It is not the shallow satisfaction of achievement or recognition. Joy is durable. It holds reverence, pride, connection, and grounding. It persists even alongside sorrow.

The Fresh Poets of the Fillmore

Three decades ago, in San Francisco’s Western Addition, a group of middle school students—labeled “troubled” by their teachers and dismissed by the city—decided to tell a different story. Guided by a youth organizer, they mapped the assets of their neighborhood: barber shops where homework got done, storefronts turned into classrooms, a bowling alley that doubled as sanctuary.

Their work culminated in a dream that felt outlandish: to perform their own raps and poems on the legendary stage of the Fillmore Theater. Against all odds, the “Fresh Poets of the Fillmore” stood under the same lights that once held Billie Holiday and Jimi Hendrix. Their words brought parents, shopkeepers, and grandparents to their feet in ovation.

This project, which predated Kohl-Arenas’ partnerships with PVI and Sipp Culture, was an early example of her own community-based organizing. It was more than a performance—it was a declaration: we exist, and we are worthy of celebration.

Tamjavi: A Festival Against Fear

Five years later and 200 miles south, Fresno’s immigrant and refugee communities were living under a different kind of shadow. After 9/11, immigration raids swept through the Central Valley, seeding fear and silence. Out of that climate, and through years of collaboration with community partners, the Pan Valley Institute (PVI) helped organize the Tamjavi Cultural Exchange Festival—a three-day takeover of Fresno’s Tower District that blended Cambodian opera, Oaxacan food traditions, Hmong comedy, Mexican bandas, and Indigenous storytelling.

Over 3,000 people filled the streets. What could have been a moment of hiding became instead an act of public defiance and joy. The festival wasn’t just about art, it was about survival. About insisting that cultures too often marginalized or criminalized could claim space, laugh loudly, and be seen.

Utica, Mississippi: Reclaiming Main Street

Across the country in Utica, Mississippi, another story was unfolding. For decades, the town had been hollowed out: its textile factories gone, its grocery store shuttered, its high school closed. Yet the Mississippi Center for Cultural Production – known locally as Sipp Culture – saw something else.

They asked residents to imagine their most beautiful food future. Elders wrote letters to future generations, describing town squares with cafés, gardens, and music. Teenagers interviewed their grandparents about recipes carried across generations.

From that process, Sipp Culture began buying back the town’s abandoned main street. What was once a symbol of abandonment is now an industrial kitchen, a farmers’ market, a performance space, and a 17-acre community farm. Founder Carlton Turner calls it “taking the keys back from the Confederacy.”

In Utica, joy looks like collard greens grown in backyard gardens, oral history circles with teenagers on the edge of their seats, and the smell of biscuits stamped with a grandmother’s three-finger brand.

Joy as Public Humanities

These stories matter because they challenge how we think about resistance. Too often, resistance is reduced to protest, policy, or opposition. But the Central Valley and Mississippi Delta remind us that resistance also looks like a story carried across oceans, a meal shared across cultures, a festival dancing with laughter in the face of fear.

The Pan Valley Institute and Sipp Culture call this agri(cultural) justice: reclaiming land, food, and culture from the same systems that once dispossessed them. But their work also embodies something larger. They show that joy itself is infrastructure and a resource that sustains movements, binds communities, and makes survival not just possible, but beautiful.

As Grace Lee Boggs once wrote, revolutions are not only about tearing down but also about creating. To create under conditions of scarcity, repression, or trauma requires more than strategy. It requires joy.

The Work Ahead

Partnerships between academics and communities, between California and Mississippi, are not simple. They take decades of trust, humility, and showing up as full selves rather than institutional representatives. They require letting go of control and letting community wisdom lead.

But the reward is immense: not only thriving festivals, gardens, and performances, but also the reawakening of imagination itself; because joy is not the opposite of struggle. Joy is what makes struggle bearable. Joy is the language of survival. And joy shared, celebrated, cultivated is what points us toward the futures we have yet to build.